In the early 2000s, Eli Lilly and Company agreed to pay up to $325 million to acquire the rights to a promising diabetes drug, one whose origins could be traced back to the grooves in the teeth of a particular North American lizard.

The Gila monster sports a distinctly pebbly coat of black and orange that mirrors the desert landscape it inhabits. These lethargic reptiles spend most of their lives underground, and eat just three to four large meals a year. This off-the-grid lifestyle makes Gila monsters quite difficult to research. Yet researchers now believe that their genome might hold the key to treating several human conditions.

That’s because this endangered lizard species inspired one of pharma’s biggest blockbusters: a class of the most successful weight-loss drugs to date.

John Eng, and endocrinologist at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in the Bronx, in 1990 discovered a hormone in the venom of the Gila monster similar to the human hormone called glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1).

Since the late 1980s, scientists believed that a gut hormone called GLP-1 could help treat type-2 diabetes. Secreted after a meal by cells in the small intestine, the hormone controlled meal-related glycemic changes through the augmentation of insulin (which lowers blood sugar levels) and inhibition of glucagon (which increases blood sugar levels) secretion. But GLP-1 is quickly degraded by our bodily enzymes.

However, this lizard hormone, exendin-4, was more resistant to enzymatic breakdown than GLP-1 and therefore lasted considerably longer in humans. A decade later, a synthetic version of exendin-4 became the first medicine of its kind to be approved for treating type-2 diabetes, which spurred the race to develop more effective and longer-lasting GLP-1 medications.

Pursuing a potent diabetes drug, scientists soon noticed that these drugs had an unexpected side effect: weight loss — although the initially did not know why.

The potential weight-loss benefits of GLP-1 agonists weren’t pursued seriously until the publishing of notable research papers in the mid-1990s, but this was for obvious reasons.

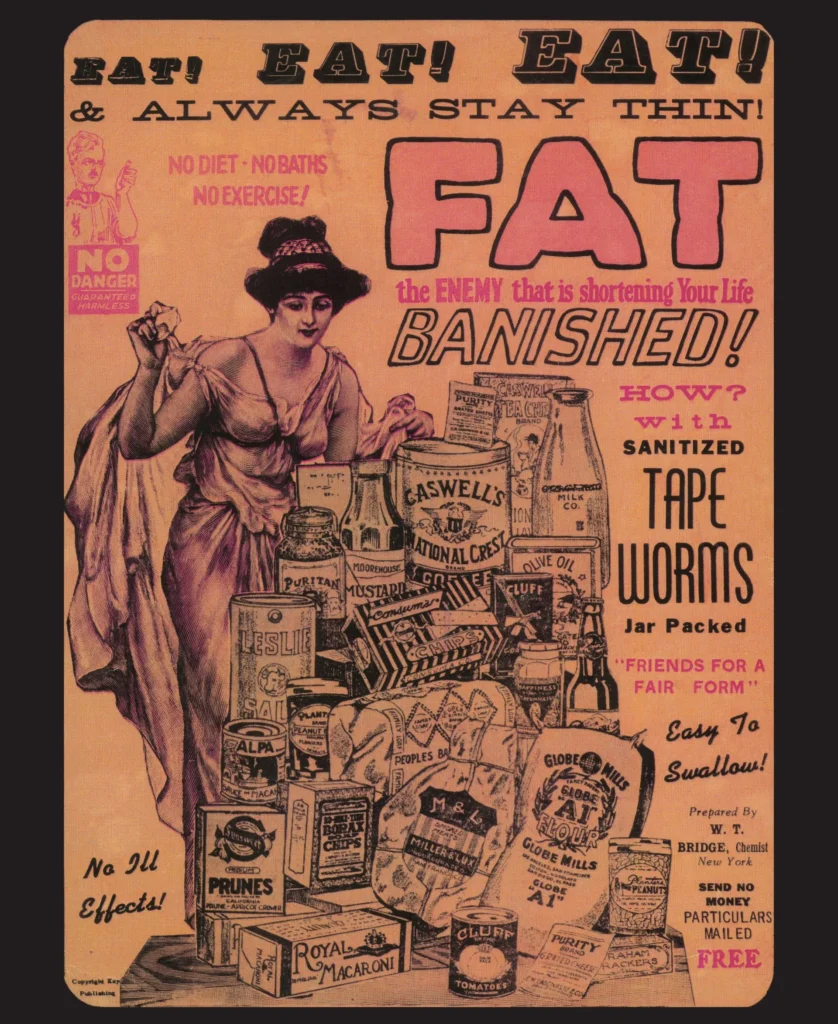

Obesity, and more notably the drugs that claim to cure it, have had a sorry past. A small group of companies — none with any notable experience in the business of pharmaceuticals — began selling these “rainbow diet pills” in the 1940, which were unicorn-themed pellets packed with amphetamines and other potent drugs at no standard formulation.

The varying colors were meant to emulate concern on the physician’s end; one paper described it as “a clearly insidious version of what might otherwise be termed as ‘personalized medicine’ today.”

These pills vehemently opposed the theoretical foundation of what physicians had learned about obesity up until that point. To bolster their drug catalog, said companies would invite physicians to all-expense-paid symposiums, education them over the all-internal etiology of obesity; tenderly coaxing them into selling potentially life-threatening drugs.

It worked.

According to a Congressional investigation from 1967, weight loss clinics earned an estimated $250 million in patients fees alone, with an additional $120 million spent on rainbow pills. The FDA would ban these pills the following year, and they largely disappeared from the market by the 1970s and 80s.

Other weight-loss drugs since have faced troubles of their own: Fen-phen, a combination selling modestly in the 1990s, was pulled in 1997 after doctors submitted data indicating that the drug caused heart valve problems. Sibutramine, sold under the brand name Meridia, was withdrawn in 2010 when it was discovered to cause adverse cardiovascular events.

But with the collective medical costs due to obesity among American adults alone in the hundreds of billions, it made zero sense for pharmaceutical companies to cease all efforts; it was only a matter of time until a successful drug emerged from all those failed clinical trials.

For years, medical science remained unyielding in its explanation for obesity. Fluctuations in weight are caused by an imbalance between calories consumed and burned, physicians were taught, and for you to lose weight you have to simply expend more calories than you consume, and vice versa.

As per this belief, the widespread notion became that excess weight reflects weak willpower. But evidence that has emerged in the last few decades shows that obesity follows a more complex pathology, and the craving that bedevil the health and the obese might just not be the same.

In 2017, one of the world’s leading organizations in the field of metabolism issued a statement that reflected on this new explanation of obesity. “Growing evidence suggests that obesity is a disorder of the energy homeostasis system, rather than simply arising from the passive accumulation of excess weight,” it said. According to the authors, obesity occurs due to two related but distinct processes: (1) sustained positive energy balance; and (2) resetting of the body weight “set point” to an increased value. The latter explains how several endogenous determinants converge to reset the body weight “set point” — essentially tricking the body into believing that it needs to retain all that excess weight.

This hypothesis, an attempt at tackling fatphobia, instead gave opportune pharmaceutical companies to cash in on years of research. An explanation for obesity that relied not on physiology, but on molecular biology gave them the perfect pathway to promote a lab-grown solution: weekly shots belonging to the GLP-1 agonist class of drugs.

In 2021, Danish firm Novo Nordisk showed data from a clinical trial where overweight and obese patients were put on a weekly dose of its GLP-1-based drug, semaglutide (sold under the brand name Ozempic), for 68 weeks. The results were dramatic: participants lost 15 percent of their body weight on average.

But that was barely scratching the surface of these potentially life-altering drugs.

Last November, emerging evidence started suggesting that the drug’s benefits extended beyond obesity. A trial, called SELECT, was conducted in 41 countries with over 17,000 people who were overweight or obese and had a preexisting cardiovascular disease, but didn’t have diabetes.

It was found that weekly semaglutide injections not only helped patients lose weight, but also reduced the risk of heart attack, stroke, or death from cardiovascular causes by 20 percent. This magnitude of effect puts it in line with other drugs used to prevent cardiovascular events, such as low-dose aspirin and statins.

Other studies reinforced these findings. Since GLP-1 receptors also exist in the heart, blood vessels, liver, and kidney, these drugs can directly affect (and benefit) these organs, as clinical trials have shown. Based on these results, the FDA in early March approved the use of injectable semaglutide to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death, heart attack, and stroke in adults with cardiovascular disease who are overweight or obese.

Then there’s the drug’s ability to interact with the brain and suppress urges, which could explain why it has been shown to affect not only appetite but alcohol consumption. People who have taken GLP-1 drugs have self-reported suppressed urges to drink and smoke. A recent study that examined the medical records of over a million people with opioid- and alcohol-use disorder found that those who were using GLP-1 drugs had, for some reason, a 40 percent lower overdose risk and a 50 percent lower alcohol intoxication risk compared to people not on GLP-1s.

But one alternative theory, one that would bring GLP-1 drugs even closer to “miracle drug” status, in their potential ability to shut off inflammation.

Research presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference showed that liraglutide, an older-generation drug in the GLP-1 family, seemed to reduce shrinkage of certain brain areas by nearly 50 percent in a U.K. trial of 200 patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease. Other studies show that semaglutide yields similar results, and these neuroprotective effects may extend to Parkinson’s disease as well.

These findings reinforce the fact that excess weight is a modifiable factor for several conditions — and that this risk factor can be modified with therapeutics like GLP-1s. But there’s a huge caveat.

Many of the ancillary benefits of GLP-1s — even those that initially seem obscure for a diabetes drug, like a reduced risk of colorectal cancer — are in line with a drug that can lead to dramatic weight loss. Obesity is one of the greatest risk factors for the development of cardiovascular and kidney disease; it’s one of the top modifiable risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease; overweight individuals have a greater risk of colorectal cancer; excessive weight can restrict breathing and cause sleep apnea; and reproductive disturbances (regardless of a PCOS diagnosis) are more common in obese women.

But these additional benefits come with a more serious implication adjoined: Due to its unwanted side effects, many people stop using Ozempic (and the like) within a year. And since most people regain most of their weight once they’re off Ozempic, they might also lose out on the downstream benefits once they stop. Many might choose not to stay on a drug perpetually to stave off a cardiovascular event or Alzheimer’s.

Since clinical trials aren’t usually designed to determine the action of a drug, GLP-1’s exact mechanism of action isn’t completely understood. As we further research these drugs, we’ll come to learn whether these effects are separate from or a fortunate outcome that follows weight loss.