The Lamen

How worried are we about a possible bird flu pandemic?

Caught in our very own pandemic, we could’ve cared less about bird flu, until now, that is.

Image: Unsplash

TWO YEARS PRIOR, an inmate in Colorado became the first person in the U.S. to test positive for H5N1 — also known as avian influenza or bird flu. Health officials and the general public were tossed into a frenzy: Had the virus already evolved to a stage where it could easily infect humans? Could human-to-human transmission be possible? The answer to these questions was a reassuring no.

The patient picked up the infection while he was involved in the culling of H5N1-infected poultry. Reporting fatigue for a few days as their only symptom, the patient soon recovered, the CDC announced, adding that other people involved in the culling operation had tested negative for the infection. The risk for the general public, therefore, remained low.

But when the second-ever case of bird flu infecting a person in the U.S. surfaced earlier this month, we were met with an altered playing field. This patient, who reported eye infection (conjunctivitis) as their only symptom, acquired the infection through cows — a first-of-its-kind occurrence.

H5N1 isn’t a new influenza strain. The type spreading today — also known as Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) — descended from a virus that was first discovered in 1996 in domestic geese in China, one that killed 40 percent of the farm birds it infected. Since then, descendant bird flu viruses have caused the deaths of over 90 million birds since 2022 in the U.S. alone, and doubled the price of eggs — documented as by far the worst such outbreak in history. But somehow, we’ve never felt as threatened as we do now.

Evidence that avian influenza is also spreading among mammals sparks panicked headlines about whether the virus could soon jump and spread between humans.

The virus has already been detected among 33 dairy cattle herds across eight U.S. states — causing decreased lactation, low appetite, and other symptoms in infected cattle. But we still don’t know the true scale of the outbreak. USDA states that they believe the outbreak in dairy cattle in the U.S. began in late 2023, initiating in Texas, and has likely circulated far beyond the 33 farms where it has been detected.

The FDA report of commercial milk PCR positivity supports the assertion. But it is important to emphasize that PCR is testing for remnants of the virus, not live virus. These viral RNA remnants are not infectious and persist even after heat inactivation at pasteurization temperatures, but they won’t infect people.

Thankfully, there has never been widespread human-to-human transmission of the virus, which is one of the reasons why risk assessment from both the WHO and CDC remains that there is a low risk for humans for this “version” of the virus.

Current capabilities of the bird flu virus provide little comfort, really, since it cannot be assumed that this will remain the case.

Bird flu transmission to humans has been sporadic. In the last twenty years, 23 countries have reported a total of 889 cases and 463 deaths (a 52 percent mortality rate) caused by the virus. However, most infections are detected in people working directly with diseased poultry.

HUMANS CAN BECOME INFECTED with bird flu if they come in close contact with infected birds — dead or alive — or with surfaces that may have been contaminated, but the occurrence is rare. To infect a host, these viruses first have to bind to certain receptors found in the cells lining the respiratory and digestive tracts. The virus currently spreading does this using one of two key proteins that make up its outer covering — known as hemagglutinin 5, or H5. This binding allows the virus passage into vital internal systems.

But because humans don’t carry these receptors in their throats, noses, or upper respiratory tracts, they aren’t really susceptible to the current bird flu strain. Interestingly, though, we do have the avian version of these receptors in our eyes, which explains why certain people may develop an eye infection.

We haven’t yet seen evidence that this particular H5N1 sub-variant is enhancing its potential to spread among humans, but we recognize that the possibility cannot be ruled out. According to Science, several vets have heard anecdotes about workers who have conjunctivitis and other symptoms—including fever, cough, and lethargy—and do not want to be tested or seen by doctors.

In the last few years, the virus has spilled over to new species in different parts of the globe: at least 48 mammal species across 26 countries have been affected. As early as 2003, the virus was seen to infect tigers and snow leopards in a zoo in Thailand. It has since spread to distant lands like mainland Antarctica, infecting foxes, seals, sea lions, and polar bears through its journey.

For some of these mammals, the route of infection is pretty obvious. Scavengers that feast on infected bird carcasses could easily pick up the virus. But usually, it’s of fleeting concern to us. But when H5N1 tore through a mink farm in northwestern Spain or started spreading among cows, we couldn’t leave things ignored — since the infection occurred in a mammal that has upper-respiratory tracts similar to humans; or one that we are largely co-dependent upon.

Moving across species allows the virus to mutate and evolve, possibly gaining the ability to infect more species. There is no way to accurately predict if the virus will acquire the capacity to spread between people, or when and under what conditions it would make the fateful leap if it does.

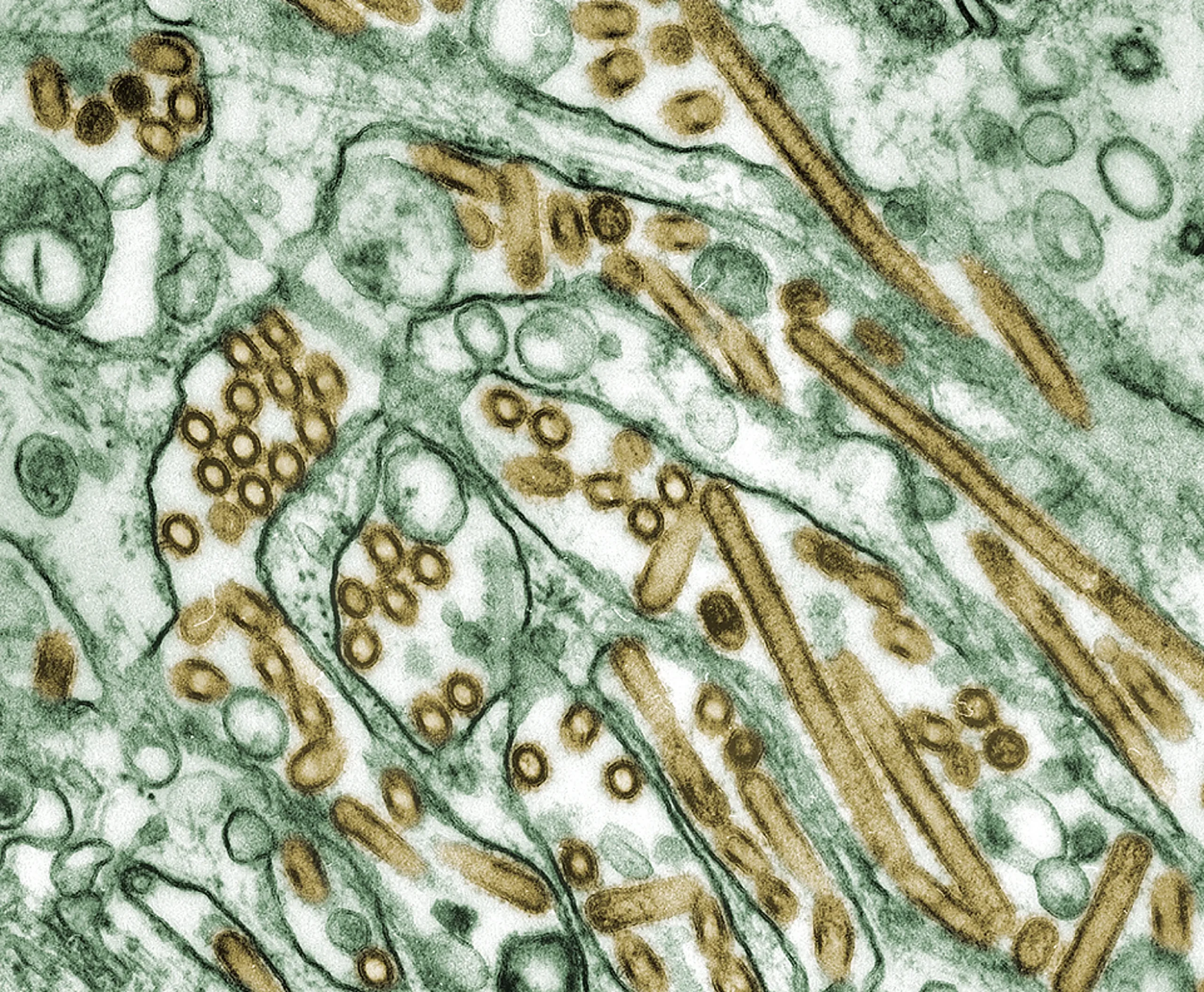

Digitally-colorized transmission electron microscopic image of Avian Influenza A H5N1 virus particles (seen in gold), grown in Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) epithelial cells (seen in green). Source: Public Health Image Library

THERE ARE TWO WAYS that influenza changes. One is the genomic errors and changes that occur when a virus replicates inside the host. The other is a process called reassortment, which is when two or more viruses “exchange” whole sections of their genomes. By this logic, the more mammalian species get infected, the more opportunities the virus has to evolve into a strain capable of a human pandemic.

Since a person acquired the virus from infected dairy cattle, the relative human risk is probably as high as it’s even been. Occasional spillover from birds to mammals is one thing, but transmission among mammals — especially those whose respiratory tracts closely resemble those of humans — is another.

What experts are paying particular attention to are pigs, often referred to as “mixing bowls” for flu species. Pigs can be infected with both avian and human versions of flu viruses. If pigs become co-infected with various types of flu, viruses gain the opportunity for reassortment, forming hybrids that can then spread from pigs to people. The 2009 H1N1 flu pandemic — which caused about 284,000 excess deaths worldwide — was caused by such a virus that jumped from pigs to people.

But we’re more prepared for an influenza pandemic.

At the first sign of H5N1 — or any other flu virus, for that matter — spreading among people would trigger a chained response of vaccine production and deployment to mitigate the damage of a potential pandemic.

The good news: The world makes a lot of flu vaccines, and has been doing so for decades. The U.S. even has some H5 vaccine in a stockpile that it believes would offer protection against the version of the H5N1 virus infecting dairy cattle.

The bad: The current global production capacity isn’t close to adequate to vaccinate a large portion of the world’s population in the first year of a pandemic. (A STAT report does a great job estimating how many vaccines we would require in the case of a pandemic, and where current production capacities stand.)

Most experts look at this as an animal health issue (at least for now) with the potential to become a human health issue. More convenient, therefore, would be to deploy vaccines that can catch the virus in its animal hosts, which would reduce the number of pathogens in the environment, substantially reducing the risk of zoonotic spillover.

The truth is, there’s no accurate estimate of how fatal a virus that could jump among humans would be. Since the 1900s, infectious diseases have proven surprisingly deadly — killing millions more in low-income countries than noncommunicable diseases do. Something that could overwhelm the healthcare system would be more deadly than it should, which asks for better preparedness. According to some estimates, COVID-19 caused two to four times greater excess deaths than the reported number of confirmed deaths. A virus highly pathogenic and with high mortality rates among birds, however, could prove even more dangerous.

Unless we work harder to contain these viruses when we first learn of them, the transmission only gets worse.